- Home

- Donis Casey

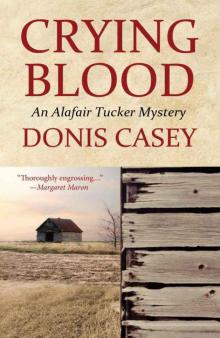

Crying Blood - An Alafair Tucker Mystery Page 21

Crying Blood - An Alafair Tucker Mystery Read online

Page 21

It suddenly dawned on him that he was alive. His ear was bleeding like Moses and the leg hurt like hell, but he was alive. And for the past couple of minutes his pursuer hadn’t been trying to alter that fact.

The man didn’t move, listening to the silence for a good while before finally lifting his head to assess the situation.

Through the bushes, he could see the toes of his pursuer’s boots protruding over the dry yellow grass three feet from his face. The man dared take a breath and raised up on his elbows.

The hunter lay on his back, spread-eagle, his hair radiating like a corona around his head. He was staring at the sky with a look of profound surprise on his face and a neat hole in the middle of his forehead.

The man emitted a sob of relief mixed with amazement. That was the goddamned, son-of-a-gun, Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, luckiest shot ever shot by a living human being on the face of this earth.

He was motionless for a minute or two, trying to calm his heart. It was hard to wrestle his mind around to where it needed to be. Instead of planning his next move he couldn’t stop himself from reliving the stupid things he had done to get himself into this situation.

But it had been so easy to kill Goingback. Just clomp him in the head when they were out in the woods together alone, then chop down a tree so it would fall on the body. A horrible accident. Nobody questioned his story or even looked at him sidelong.

He told the widow that he was beside himself with remorse. By that time he had lived in the Indian Territory long enough to know that the Creek believed even an accidental death had to be made right. The tribal council had thought it only logical that he should marry the widow and support her and her children for the rest of her life. The widow was amenable. Goingback wasn’t much of a husband in the first place.

And everything had gone so well for so long! They built a sturdy house, cleared land for a sawmill, built a road to the highway so that when the time came he could haul wagon-loads of finished lumber to the railroad. Ten damn years he had worked like a coolie. He was satisfied with Lucretia and got along with her children. They even had the two boys of their own, bright little lads.

Then the government had decided to give each and every member of the tribe a piece of land for his or her very own. Many chose plots on or near where they already lived. Some refused to choose and had plots assigned to them. Lucretia got hers, which was really his since she didn’t care one way or the other. The children all got theirs, adjoining their mother’s. Things couldn’t have been any better. He was the patriarch of an empire! Him, who had left Ireland with nothing but the clothes he stood up in.

And then the KATY had decided to put their railroad spur somewhere else. That was bad enough. But after the shock wore off he realized he may be able to salvage the situation by building another road. His stepson’s allotment abutted the Ozark Trail.

Now, the widow’s son had worked along side of him for years, happy as a lark. But all this allotment business had put the youth out of joint. That land belonged to all the people together, he said. He wasn’t going to take it up, he said. And even if the government forced the boy to take title it wouldn’t do the man any good. After the new law went into effect in a few months, White folks wouldn’t be able to buy land off of full-bloods for twenty-five years.

It was all so complicated. Killing Goingback had been so easy. And if any of her children died without issue the widow would inherit his allotment to add to her own.

But everything had gone awry. The man was getting old and the widow’s son was young and quick. They had gone out together that night, just the two of them, like they had many times before, intending to hunt in the morning. The lad arranged his blanket beside the fire and went to sleep, or so it seemed. One blow of the axe ought to have done it. But the damn kid had ears like a bat. The axe came down on bare dirt where the young man’s head had been a split second before.

They were both on their feet then, and looked each other in the eye. The lad didn’t even look shocked. You could tell by his expression that he knew everything. He had figured it all out in the time it took for that axe to plunge into the earth.

That’s also how long it took the man to see that he had been mistaken about who was likely to die this night. He took to his heels.

Damn, if he just hadn’t tried to take the easy way out. He and the lad could have figured something out, come to an agreement.

The man leaned back and stared at the sky for quite a while, trying to think. But his mind was unable to function properly. A handful of dirt and small stones cascaded down the sheer bank behind him, loosed by a gust of wind. He blinked and scrubbed his face with his sleeve to remove some of the blood and sweat fouling his vision, then cast a quick look around the brushy clearing. No boy to be seen. Perhaps in his panic he had just imagined that he’d seen the young face at the edge of the woods.

He felt the side of his head where his ear used to be. It stung like the devil but was clotting up already. What a mess. He attempted to stand but his shot-up leg wouldn’t support him. He regarded the wound in his thigh. Not bleeding much, certainly not pumping blood. No artery hit, so he wasn’t in immediate danger of death. He’d have to have the slug out, though, before it poisoned his blood.

He was just beginning to form a plan of action when he heard movement and sank back down.

His wife was standing on the brushy edge of the dry creek bank with the boy behind her. He caught his breath and said nothing. He didn’t think she could see him, still half hidden behind a bush under the overhang.

The woman crossed the wash and bent over the hunter’s body, her face impassive. The man puffed out a breath. She never failed to surprise him with her stoicism. He liked to think that if his own mother had found him dead she’d shed a tear or two.

The boy tugged at the woman’s sleeve and whispered in her ear. Her gaze lifted, eyes black and hot as coals, staring right at him. She straightened and walked to his hiding place with the boy on her heels. She parted the brush and stepped into the space under the ridge. Her eyes went to the hand axe that had taken off his ear, still embedded in the bank.

The man gasped and scrabbled as far back into the little cave as he could manage. It was a desperate move, but futile. She was standing over him now with the axe in her hand.

“You killed my son,” she said. Her tone was matter-of-fact.

“Lucretia, he tried to kill me! I had no choice!”

“That ain’t what Ira says.”

He gaped at the small figure with the intense expression who was standing behind his mother. “Ira, you saw, laddie! You saw!” He despised the wheedling tone of his own voice but couldn’t do anything about it. “It was self-defense!”

The blank expression on the kid’s face was impossible to read. For a moment the man was hopeful. “You wouldn’t want for him to kill your dear dad, would you, boy?”

Ira didn’t have an opportunity to answer. Lucretia took a two-handed grip on the axe handle and brought the blunt edge down on the man’s head with all the force she could muster. The man sprawled unmoving in the dirt, one of his eyes nearly popped out from the force of the blow. He hadn’t tried to defend himself. He hadn’t had time to realize what was happening.

She knelt, leaned close to check for signs of life, and started when he snatched a handful of her long black hair and drew her down to breathe his curse into her ear.

I’ll claw my way out of hell and make you pay.

Lucretia wrenched herself free. With a blow from the sharp edge of the axe, then another, she sent him to the hell he expected and deserved. She stood and stepped back to inspect her handiwork, then placed the axe down on the ground.

Ira and his mother regarded one another for a long time before she said, “We got to bury him.”

Ira nodded and gave Lucretia a sign to move away from the mutilated body. Small and light, he grabbed one of the dead tree roots protruding from the cliff face and hoisted himself hand over hand to the top. It

was hard to negotiate the precarious overhang, but he was strong and lithe and managed to swing himself out enough to grab the grassy lip of dirt and haul himself up. Even his slight weight caused a crack to open in the overhang, but he had to jump up and down on it for a bit before it gave way. He sledded down on top of the mini-avalanche and arrived at his mother’s feet with only a skinned knee and a bruise on the heel of his hand. He got to his feet and dusted off the seat of his trousers.

The man with the busted head was good and buried. Only the fingers of one hand protruded from the pile of scree and red dirt that had once loomed over the creek bed.

Ira and Lucretia turned back to the hunter Chitto, who was staring upward relentlessly, as though surprised at the sight of heaven, and made their plans to take him home.

Producing, Preserving, and Cooking Meat

Butchering Time

Shaw Tucker was a breeder of mules and work horses, so pork wasn’t a primary part of the Tuckers’ income. However, he kept one or two breeding sows to provide the family with meat and made a little money on the side by selling the surplus piglets to his neighbors. But like everything else Shaw did on the farm, he approached the raising of pigs as an art, and the animals he sold were much in demand because of their high quality meat.

Shaw kept a special penning area for hogs being readied for slaughter. It was a good-sized sty, big enough for four large hogs to have individual shelters, troughs, and room to roam. Shaw always chose animals that were big and healthy but not huge or too fat. Not because of any extra effort that may be entailed in the slaughter or the processing. It was a hard, miserable job no matter how big the carcasses were. But smaller, leaner pigs with just the right amount of firm, white fat made for higher quality meat and lard. Had Shaw been raising pigs for a large-scale business, he more than likely would have fattened them on more economical feed corn. Since he never had very many hogs to feed at once, he decided he’d rather be a little persnickety about their eats and get the best meat out of them he could.

So he chose two or three likely shoats in the spring and moved them into the equivalent of a hog luxury hotel, where they were fed apples and hay, milk and molasses, as well as table scraps. They were regularly put out to pasture and sometimes turned out in the woods to root for acorns and grubs and any other delectable morsel they could find, and to get some exercise and fresh air. Alafair swore that pigs who ate meadow flowers had the tastiest meat of all. Shaw had never heard Alafair’s peculiar pork belief before she came into his life, but since she was the one who was responsible for turning much of the pig into a year’s worth of meat products, he respected her opinion and saw to it that his pigs spent most of their one and only summer of life in a flowery pasture.

In the fall, after the first freeze of the season, two well-grown hogs were moved from the feeding pens into the much smaller retaining pens next to the processing area behind the barn, coaxed along the path with a bag of apples and prodded in the right direction with a cane.

The hogs spent their last two days in small pens close to the slaughter area, fasting but drinking plenty of clear well water. A few hours before they were to meet their doom, Shaw fed each of them a small pan full of sugar. Just as Alafair was convinced that a diet of wildflowers flavored the meat, Shaw’s Irish stepfather had taught him that a final meal of sugar made the pork sweet. Besides, the hogs loved it.

Some years Shaw raised a calf for slaughter, or a goat or two, and when he did, he made very sure to kill the beast in isolation so as not to upset its companions. But when it came to pigs he never bothered. Swine are smart but totally unconcerned about each other’s fate. In fact, if a pig died at night in the presence of its fellows, Shaw seldom saw the carcass. There wouldn’t be a bone or hair left by morning, thanks to its cannibal litter mates.

Shaw sent Charlie out to scrub the pigs down the day before slaughter. They didn’t stay all that clean in their little pens, but it helped and they enjoyed it.

A block and tackle was rigged over a stout tree limb and a second huge iron cauldron sitting close to the trunk was filled with water the day before. First thing in the morning, Shaw lit the fire under the cauldron, and by the time the hogs were moved into the chute the water was already steaming in the cold air.

Once the hog was confined, Shaw killed the animal with a single shot in the forehead. His father and grandfather had killed pigs by sticking them in the carotid artery with a sharp knife. If a pig wasn’t properly bled the meat could spoil. Besides, no self-sufficient homesteader ever wasted any part of an animal, including its blood. The first hog slaughter Shaw ever witnessed when he was a boy was a bloody affair. The butcher had stuck the pig and then hauled it up by its hind legs to hang head down and bleed out while it was still conscious. The squealing of the dying pig gave the young Shaw nightmares for a month.

His father had usually stunned the hog with a hammer before slitting its throat, but that wasn’t much more pleasant for a boy to witness. Shaw had never seen a hog shot until the first time his stepfather slaughtered. He figured he and his brothers must have looked startled, because Peter McBride had winked a lively blue eye and assured them that if they looked sharp and got that hog up the tree in good order, its heart would keep beating long enough to insure a good bleed.

Shaw didn’t know which method a professional butcher would prefer. But as for him, he’d never lost a carcass to contamination, and besides, if he never heard another dying pig that would suit him just fine.

As soon as the hog dropped down dead, Shaw opened the gate and threw a sturdy rope around one hind leg. He and his helpers hauled the animal out and hoisted him up off the ground with the block and tackle. Shaw quickly slit the pig’s throat, careful to sever the large veins and arteries. The blood flowed in a pulsing stream into a large tub on the ground beneath.

Proper bleeding took several minutes, so the boys washed the pig yet again and Shaw cleaned his knife before leaning against the tree with a great sigh. Eventually the pulsing stopped and the stream became gouts, then drops, and finally ceased altogether.

They removed the tub full of blood and rotated the block and tackle enough to suspend the carcass over the cauldron, then lowered it head first into the scalding water. Three or four minutes of scalding was long enough to loosen the hair on the hog’s skin.

Then they hoisted the hog out and put it on an enormous sled for transport to the covered butchering house just a couple of yards away. It took two or three men to maneuver the animal onto the table, where they scraped off the remaining hair and removed the hooves. Farmers who butchered meat for a living often used a gambrel, a tool especially made for hoisting a carcass for cutting up. But Shaw’s main business was horses and mules, so whenever he butchered an animal he used the utensils he had at hand, which meant a piece of harness equipment called a singletree. He inserted ropes through the Achilles tendons, attached them to the singletree and once again hoisted the carcass to hang head down from a rafter in the center of the shelter.

The young men proceeded to sluice down the table and the sledge while Shaw removed the animal’s head. Just about the time he was severing the gullet Alafair and her daughters joined them, all dressed as scruffily as the men and boys. The killing was done. The hard work of butchering and preparing the meat was about the begin.

Alafair and the girls filled washtubs with water as Shaw carefully split the hog open from stem to stern, careful not to pierce any organs. The intestines slopped out, but were still attached inside so never hit the ground before Shaw could cut them loose. He didn’t check first to see if Alafair was at his side, ready to take the internal organs away in a tub. She always was.

Alafair and one of the boys hauled the tub of innards to the table where she and the girls separated out and washed the individual organs. Her aides cleaned the intestines while she trimmed up the heart and chopped it up for chilling. She trimmed off as much fat as she could to save for making lard. For years Charlie was in charge of cleaning the hog�

��s head, at least while he was still young enough to get a perverse thrill out of cutting out brains and eyeballs.

As the women began the work of preserving the innards, the men thoroughly washed the now-organless body cavity. Then they left the carcass suspended from the ceiling while they repeated the whole bloody process with the second hog.

Alafair’s Recipes

Quail Pie

Quail are delicious little birds that can be used in any recipe that calls for chicken. Keep in mind, though, that the bobwhite quail that Shaw and the boys shot on their hunting trip in 1915 are smaller than chickens, so it’ll take more of them. Since they have lived their lives in the wild, quail are also tougher than home-grown poultry, so often game birds are ‘hung’ for a few days to help tenderize the meat. But if the birds are young they can certainly be cooked fresh.

There are innumerable ways to make quail pie, both simple and complex. The easiest is to cut the quail into pieces and fry it in butter. Take the birds out of the skillet and mix the pan juices with a little flour to thicken. Remove the meat from the bones, arrange the quail in a baking dish and pour the pan gravy over all. If the quail are dry, add some bacon on top of the quail meat. Top with pie crust and bake for 20 minutes or so in a hot oven (400 degrees) until golden brown.

The quail pie that Alafair took to her in-laws’ house for Sunday dinner was more like a traditional pot pie. The quail were boiled in salted water until tender, then removed from the bones and returned to the broth while she sauteed an onion in butter in a skillet. When the onion began to brown, she added two or three tablespoons of flour and stirred until smooth, then added in the quail meat with its broth and cooked it over a low flame until the mixture thickened. She then added a couple of cups of cooked vegetables—peas, potatoes, carrots, winter squash, sweet potatoes—whatever was on hand, and poured the whole thing into a deep baking dish. She then covered it with a pie crust or biscuit dough and baked as above.

The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Valentino Will Die

Valentino Will Die Hell With the Lid Blown Off

Hell With the Lid Blown Off Crying Blood - An Alafair Tucker Mystery

Crying Blood - An Alafair Tucker Mystery The Old Buzzard Had It Coming: An Alafair Tucker Mystery

The Old Buzzard Had It Coming: An Alafair Tucker Mystery Forty Dead Men

Forty Dead Men All Men Fear Me

All Men Fear Me The Drop Edge of Yonder - An Alafair Tucker Mystery

The Drop Edge of Yonder - An Alafair Tucker Mystery The Sky Took Him - An Alafair Tucker Mystery

The Sky Took Him - An Alafair Tucker Mystery Hornswoggled - An Alafair Tucker Mystery

Hornswoggled - An Alafair Tucker Mystery The Old Buzzard Had It Coming

The Old Buzzard Had It Coming The Wrong Hill to Die On: An Alafair Tucker Mystery #6 (Alafair Tucker Mysteries)

The Wrong Hill to Die On: An Alafair Tucker Mystery #6 (Alafair Tucker Mysteries)